By Kevin Mitchell

Often overlooked in favor of bigger water and bigger fish, creeks are an essential part of the western Massachusetts fishery. Winding down forested hills through ancient plunges, the area’s small streams house some of the wildest fish and most precious experiences for miles in any direction. Whether just embarking on the journey of fly fishing or tallying years of experience, plying the cold, babbling flows of an exquisite piece of small water is an essential pleasure in this region and throughout the whole of New England. This piece will cover some of the most important ideas and considerations in both approaching and achieving success on small water.

Geography

Throughout western Mass, a lot of streams source from small reservoirs and ponds in areas of higher elevation and descend along rugged valleys towards confluences with bigger rivers. East of the Connecticut River, many source waters are situated along the ridge adjacent to the Quabbin Reservoir, from where they meander down from east to west into the flat land of the Pioneer Valley and ultimately the Connecticut. The one exception would be the small streams that terminate into the Millers River which runs laterally (east/west) unlike the CT which runs north to south. In the west, the watershed is much more complicated owing to the complex topography of the Berkshire Mountains. Here, creeks descend perpendicularly along major river valleys before confluencing with rivers like the Deerfield, Westfield, Housatonic, Hoosic and the like.

Creeks east of the Connecticut tend to be characterized by minor riffles, flat runs and deep pools. The trout in these areas tend to be stocked. However, the further one pushes upstream into higher elevation on such systems, the prevalence of both turbulent pocket water and wild/creek-born fish increases. West of the Connecticut, creeks tend to be much more rugged as they quickly descend the steep, ancient river valleys typical of the Berkshires. Most systems here are characterized by pocket water and a much higher prevalence of wild fish, although stocking does occur in some streams.

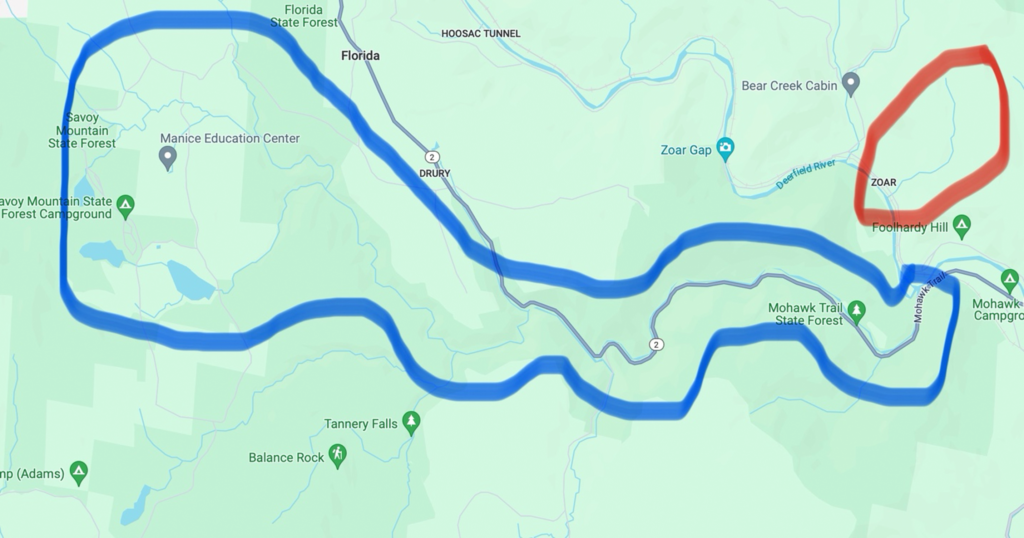

When prospecting and looking at the map—whether in the east or the west—it’s a good idea to focus attention on longer systems that either source from a reservoir and/or are fed by several smaller branches. Although a creek might be visible from the map, know that not all blue lines are created equal with many being simply too skinny to fish productively. In general, the longer the system and the more stable the source water, the more viable it will be. Take the graphic below for example:

Highlighted in blue is the Cold River system, a tributary of the Deerfield River. Notice its complex watershed with multiple arms feeding the main stem as well as a few reservoirs. Just looking at this from the map, we can pretty safely assume that this creek system is robust with plenty of water feeding into it from multiple sources (so long as there’s been enough precipitation). Looking across the Deerfield at the small blue line highlighted in red, we notice that its very short with no significant sourcing visible. In situations like this we can generally assume that this is likely just a trickling brook at most and therefore isn’t really worth our time.

Beyond topography, another important geographical consideration is the nature of a system’s surrounding banks. Because the area’s streams don’t source from high elevation snow melt like is common in the western US, tree cover is essential to the health of a creek ecosystem, especially in terms of supporting cold water fish reproduction. Trees provide shade which keeps water temperatures down. Areas that have been deforested—for example the lower reaches of the (east) Mill and Fort Rivers—heat up much faster and do a poor job of supporting trout of any origin and especially those of wild reproduction. For this reason, it’s best to stick to forested areas, especially in pursuit of wild, naturally reproducing fish.

Another note on trees: During winter when the cover of foliage has fallen, trout both wild and stocked/holdover will generally seek out a creek’s deepest pools in which to spend the coldest months. Come springtime and the return of cover from overhead foliage, fish will redistribute and begin looking towards surface forage again. The difference in dry fly productivity in the first week of April versus the last week can be night and day for this reason.

Equally important to the makeup of a creek’s banks is the nature of its bottom. Fish will generally seek out areas of low contrast in which to hold and feed, which means that they will usually avoid areas with clear, often sandy bottom where they are in higher contrast and therefore more visible. Instead, trout will usually hold in areas with a lot of substrate or rock on bottom in order to better camouflage themselves from view at the surface; the exception being depth, which provides cover. Because flows in most small streams fluctuate significantly, these low contrast, fish-holding areas are often in a constant state of change as high water pushes bottom cover around and redistributes it.

A final note on geographic considerations: Massachusetts does not delineate wild trout streams so stocking occurs in many systems that also support wild fish. Stocked fisheries can be easily found using the state stocking report, and while no such graphic exists for wild fish, a few key considerations can help lead one to the wild trout. Keep in mind that wild trout, regardless of species, are ‘indicator animals’ whose presence, or lack thereof, signals the health of a given stream system. Characteristics like cold water, ample cover both above and below the surface, robust forage and the like are essential elements to natural trout reproduction. As previously mentioned, these attributes generally become more common the higher upstream one traverses in a system. In many creeks, these areas are also a good distance away from logical stocking locations which are usually situated along easily accessible roadways and bridges. While some stocked fish survive harvest and may travel towards quality holdover water, keep in mind that most stockies will not survive past one year in the creek.

In terms of species relative to geography, wild brook trout, which are native to Massachusetts, can be found in a lion’s share of the region’s small streams. If the previously stated elements necessary to their existence and reproduction are present, chances are you will find some make of a brookie population. As for wild brown and rainbow trout, the list of requisites is a bit more complex. Because neither species is native to Mass, creeks generally need to connect with larger systems—both moving and still water—which support wild browns and/or rainbows in order for wild populations to persist in the adjoining creeks. For instance, one is much more likely to luck into some wild browns on a Deerfield River tributary than one off the Millers River because the prevalence of naturally reproducing brown trout is much higher in the former.

Technique

Arguably king among creek fishing techniques is dry fly fishing. Most creek-dwelling fish will happily take a well-presented surface imitation for a majority of the year—usually April through October in most creeks—and for many there’s really no comparison to the exhilaration of an aggressive surface eat. Small water is doubly productive for dry flies because you don’t necessarily need to see fish rising in order to elicit takes. Of course, fish do rise to naturals in such fisheries, but these instances are often easy to miss in the turbulent water typical of many creeks, especially those descending from elevation through pockets and plunges. In many cases, placing dry flies in logical spots along current seams, in front of and behind pieces of stable structure (like rocks), along bank undercuts and the like will pull bellies off bottom so long as the presentation is drag-free.

Admittedly often less exciting but usually more productive are nymphing techniques. In general, there are three main categories of creek nymphing to keep in consideration: dry droppers, contact and indicator nymphing. Dry droppers are particularly fun as the dry fly, which acts as a strike indicator, could always get eaten itself. Additionally, fish often have little time to catch up to flies in the confines of creeks, so dry droppers can be very productive both to slow rigs down a bit in fast pockets and punch down into areas that hold fish but might make it tough for them to rise.

Contact nymphing is an extremely productive technique while creek fishing as it allows one to methodically work every lane and seam that might hold fish. The jig flies most commonly used for contact nymphing do a phenomenal job of punching through upwells in difficult to penetrate pockets, areas that often support any given creek’s larger fish. The other advantage to this technique is its lack of seasonality, usually performing just as well in May as it will in November.

Indicator nymphing can be productive but does become somewhat superfluous during the warmer months when dry dropper rigs can all but replace indicators. In colder weather when fish are reluctant to eat at the surface and dry flies can appear out of place, an indicator can be a smart move but keep in mind that fish can spook easily in small systems. To avoid putting them down, think about using the smallest firm-body indicators available if not a yarn/poly-material one altogether.

Lastly, and often a bit overlooked in creek fisheries, throwing streamers can be a roaring good time. In longer runs and other roomy areas, quick stripping small imitations of dace, juvenile trout, etc. can often put a creek’s biggest fish on the move as they chase down what appears to be a high value meal. In more confined spaces, swinging streamers from an upstream vantage can be extremely productive as well. In any case, it’s best to fish streamers on short leaders that allow one to keep good contact to the fly. The choice between a floating or sinking fly line is largely dependent on the characteristics of the given creek, however, a floating line will be much easier to manage in tight spaces and will do fine to get flies in front of fish so long as they are weighted enough.

Gear

Like in most fisheries, the main consideration when selecting rods and reels for creek fishing is technique. For dry fly and dry dropper fishing, some prefer a short, light stick like a 7’6” two or three weight. This option makes both casting and navigating the densely wooded streams typical of western MA much easier given how short the rod is. Others prefer to sacrifice maneuverability for the added reach a 9’ rod provides, often allowing one to keep line off the water, minimizing drag in the complex current systems typical of many creeks. Ultimately, rod length is a bit up to personal preference for dry flies and droppers, but it’s usually the most fun and challenging to utilize rods of lighter power, generally in the 0-4 weight range.

For contact nymphing, one will generally want to select a rod that is built specifically for the technique. A 10’ two or three weight paired with a well-balanced reel and mono rig will be best, however, the tactic can be accomplished with a more general-purpose stick so long as it has enough reach and soft action to maintain solid contact to the fly through the drift.

For both indicator nymphing and streamer fishing, you can’t go wrong with a 9’ four or five weight, either of which should do well to manage the additional weight of small indicator and streamer rigs.

Fly Selection

Despite the fact that many creeks often support robust forage diversity, fly selection is often nowhere near as important as it can be on larger systems. Likely owing to both a lack of fishing pressure and ample food opportunities, many creek fish will take just about anything that’s properly presented, depending on seasonality of course. During the warmer months, a high floating dry fly which can take the punishment of lots of eats is a smart choice; examples including the PMX, stimulators and other elk hair patterns, foam-based bugs and the like.

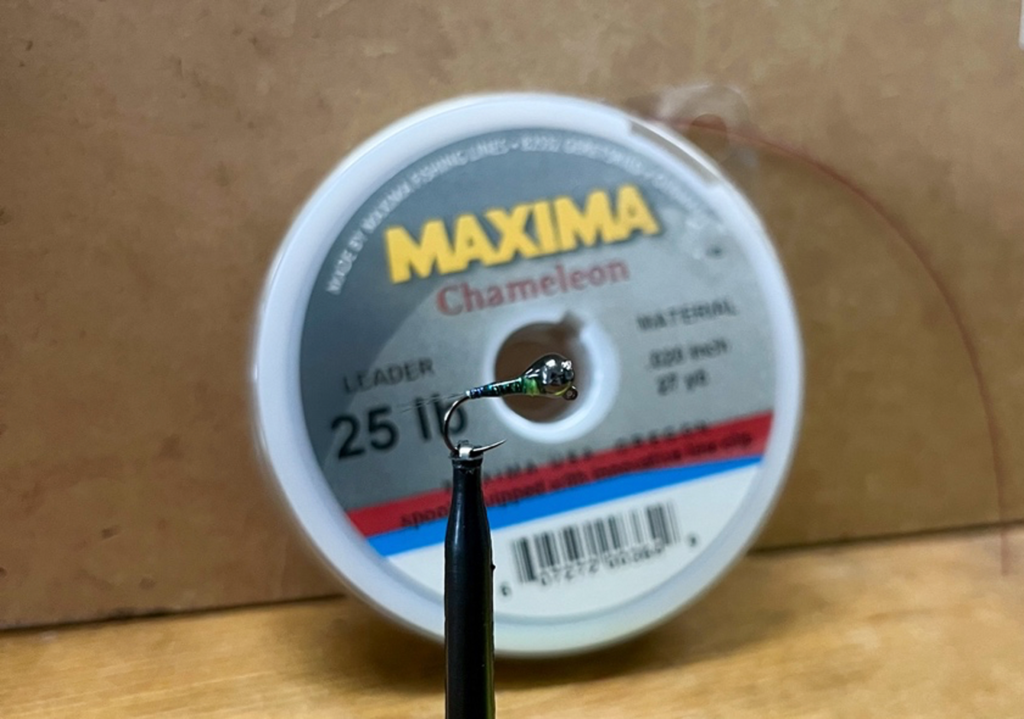

For nymphs, there’s limited need to stray from the time-tested classics. Pheasant tail and hare’s ear variations, small stoneflies, copper Johns, etc. will have no problem eliciting takes. Whether contact nymphing or not, it’s often a clever idea to throw flies on jig hooks regardless of the specific tie. Owing to the jig hook’s angled eye, flies punch down much faster than presentations tied on traditional hooks, a potentially massive advantage in small creek systems where you might only have just a few feet of drift in a given pocket or area. From the tying perspective, consider oversizing tungsten beads (based on hook size) for added speed on the drop.

Streamer selection is no different in terms of necessary complexity, or the lack thereof, as woolly buggers and zonker flies will convert just about any fish looking to take a streamer. Like nymphs, the most important consideration is weight and ensuring that your presentation is getting down far enough, especially when throwing a floating line. At the tying bench, add weight via lead-free wire, oversized beads or coneheads and consider tying streamers on jig hooks where the same principle that allows jigged nymphs to drop quickly will also apply to jig streamers.

Despite being often overlooked in favor of larger fisheries, western Massachusetts’s small streams truly are some of the wildest and most precious waters for miles around. Hopefully this piece has shed some light on the key considerations to successfully approach and achieve success on our beautiful local creeks. Please make sure to reach out if you have any questions about what we’ve covered here. If you’re interested in submitting your own piece to be posted on our blog, please send an email to brian@deerfieldflyshop.com with a brief description of the topic you’re interested in covering. As always, thank you for your continued support of the Deerfield Fly Shop and we hope to see you in the creeks.